Gérard Garouste at the Pompidou Center

[18.10.2022]“It’s not so important that people know the stories my paintings evoke. They must feel free… allow themselves to be surprised or even shocked. On the other hand, I personally need these subjects, I question them, I work them like the words of an unknown language until they allow me to paint…” – Gérard Garouste, 2022

Step into another world: until the beginning of January, the Pompidou Center is hosting a retrospective of Gérard GAROUSTE (1946)’s ‘hallucinatory’ creations. The wisely-chosen chronological exhibition route adopted by curator Sophie Duplaix provides useful insight into the evolution of the poet-painter’s work which, taken as a whole, resembles a frantic sarabande. At the same time, the Parisian gallery Les Arts Dessinés will be showing his work, in collaboration with Édouard Cohen, on the Book of Esther (Megillah).

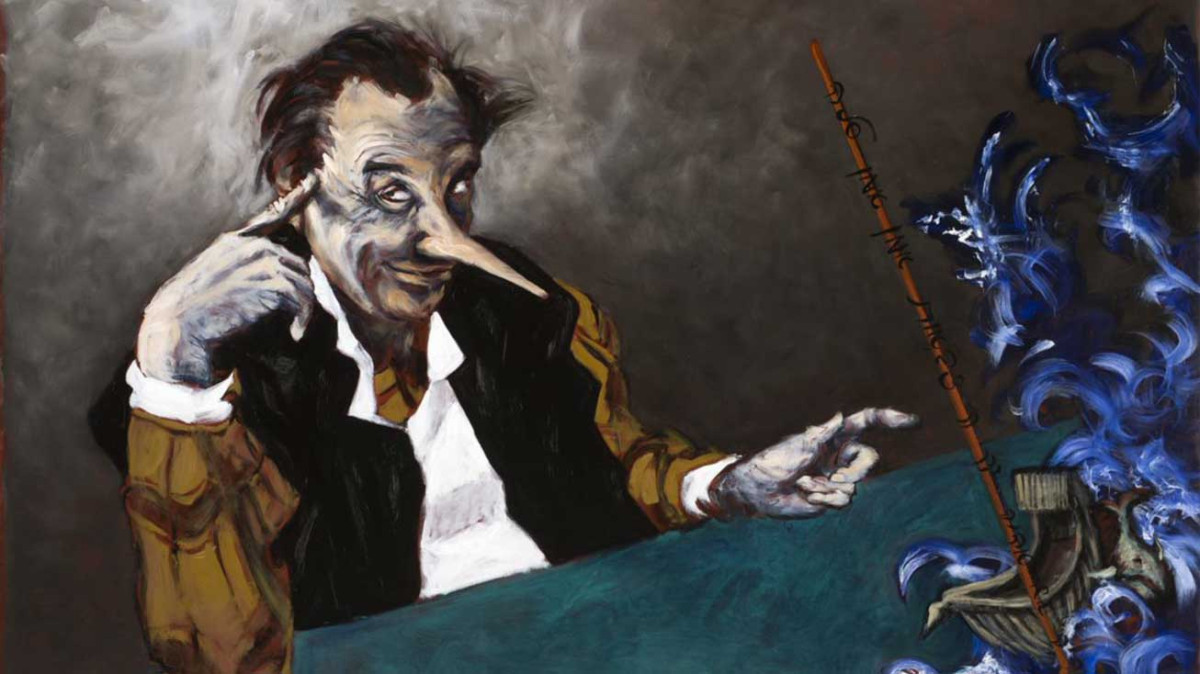

Gérard Garouste, Pinocchio et la partie de dés, 2017

A turbulent path

The Pompidou Center retrospective attempts to ‘identify’ Garouste via nearly 120 paintings, most of them very large formats, plus an installation titled Dive Bacbuc. Garouste grew up partly in Burgundy, an area full of tales and legends that was a mini-paradise for a young boy whose mind naturally tended to wander and eschew concentration. His father sent him to the Collège du Montcel, a crammer for dreamers from bourgeois families, where he met Jean-Michel Ribes, Patrick Modiano, the son of Jean FAUTRIER and François Rachline. Later, at Paris’s prestigious school of Fine Arts (Beaux-Arts), he was frequently absent from his master’s studio. Everything he knows about pictorial technique – in its most material and physical aspects – he claims to have learned from the restorers at the Louvre Museum. Investigating and scrutinizing images and words: Painting, he said, is my grammar. The canvas gives something to read, but it is also a screen that hides the meaning of the painting. In short, it’s a big lie, but one which is declared, like a child who paints his dreams while telling them: does a liar who admits he is lying tell the truth? Garouste is constantly attracted by what is concealed. He admits to feeling lost when reading Dante’s Divine Comedy: the more details Dante gives about Hell, the less the reader feels he is really there. His series inspired by the Italian poet may well be figurative in nature, but at first glance, there is little that can be understood. By his own admission, it is the interstices between two paintings that must be interpreted.

In search of lost meaning

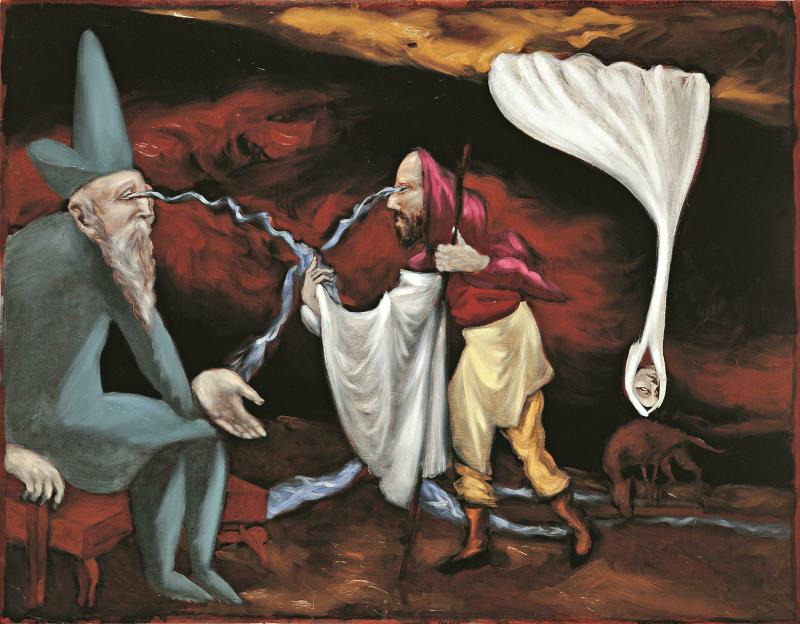

Gérard Garouste, La Croisée des sources, 1999 – 2000

Obsessed with origins, he explored the depths of history, the heritage of the Old Masters and the myths. As though producing figurative work in the conceptualist-obsessed early 1980s was not sufficiently non-conformist, and claiming credit for GRECO or RUBENS was not enough, Garouste made a point of constantly returning to classical sources: the Bible, the great texts of Greek mythology, major historical authors, from Cervantes to Rabelais. Regarding the latter – who drew the wrath of the Church and risked being burned at the stake for his poem Dive Bacbuc – Garouste says that there is an accessible face to Rabelais, which is his humor, and another esoteric face, to which one must to be initiated and which is intended to be passed on. Garouste’s canvases, made up of associations of ideas, may be either disturbing or joyful, some occupied by fantastic animals, others with dislocated bodies. His paintings are haunted by anamorphoses and personal and mythological references.

Always seeking to dissect the meaning of life, Garouste explores exegesis and takes up the figure of the river: before the Bible the believer is constantly before the same immemorial river of the Scriptures, but never before the same water, or the common sense of the meaning given to them. He learns Hebrew, where the words have at least four meanings which sometimes have no connection between them, as in his painting the Donkey and the Fig. The interpretation by association of sound or idea transports him. In 2014, he immersed himself with a master in the Talmud and converted to Judaism. Was this initiative intended to ward off his family history or to redeem the faults of his father? In 2009, with Judith Perrignon, he wrote L’Intranquille. Autoportrait d’un fils, d’un peintre, d’un fou (The ‘Excitable’, Self-portrait of a Son, a Painter, a Madman). The book opens with a description of his feverish research to confirm a persistent hunch that emerged after the death of his father. Armed with personal notebooks and a diary, he discovered that Henri Auguste Garouste, a convinced anti-Semite and opportunist Nazi-collaborator, acquired looted Jewish shops during the Occupation (including the furniture company Levitan) and that the warehouses of the family business housed furniture looted from the apartments of Parisian Jews. L’Intranquille describes above all his chaotic life-journey and his clinically bipolar world, which kept him away from paint brushes for nearly ten years. He nevertheless managed to found a family with Elizabeth GAROUSTE (1946), his childhood companion, herself a designer and artist.

Turbulent prices…

After a busy period designing shows at the Palace (famous Parisian discotheque between 1978 et 1984), he caught the eye of major art dealers. After an initial exhibition at the Durand-Dessert gallery, he was spotted by Leo Castelli during an exhibition of young French talent in New York (1982). There followed several public commissions including decorations for the Elysée Palace, sculptures for the Cathedral of Evry, a monumental sculpture for the BnF France’s National Library. The current retrospective at the Pompidou Center clearly bears the mark of the tenacity of Garouste’s current gallery, Daniel Templon.

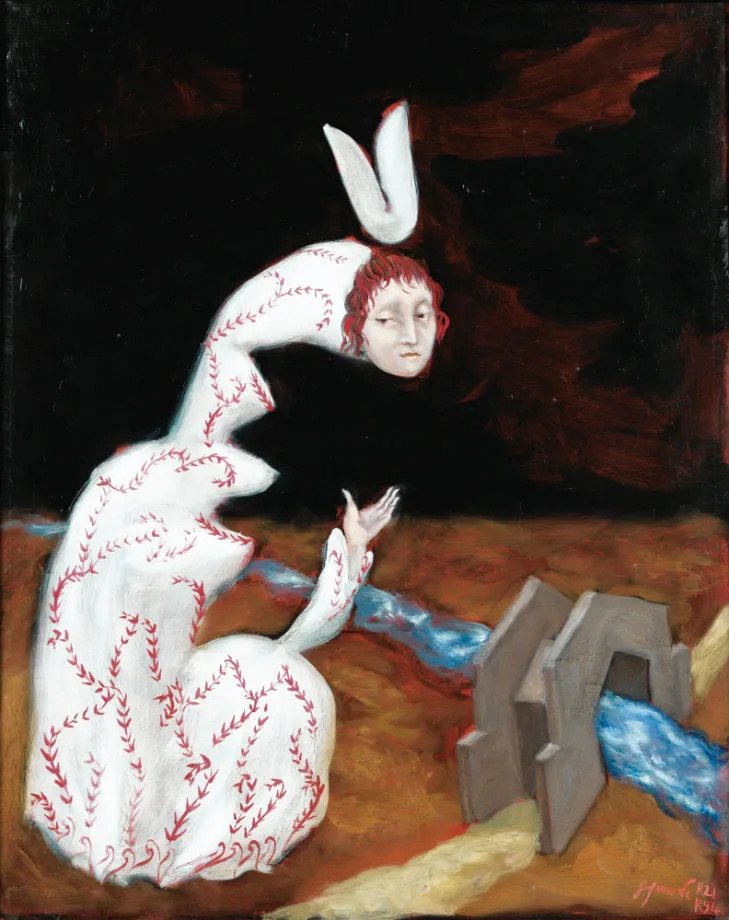

Gérard Garouste, L’Alliance, 1999

Garouste’s market has remained largely confined to France, notably because his auction prices have suffered from his episodes of mental health instability. Leo Castelli gave him a chance in New York, but he couldn’t produce enough to fuel his growing success. However, over the last twelve years there have been signs that his market is expanding: in 2017, one of his paintings, L’alliance, fetched over $100,000 at Pierre Bergé & Associés in Paris. Among French painters born after 1945 (like Garouste), few have crossed this threshold. Only 11 of them have sold in France for auction prices above $100,000: Robert COMBAS, Philippe PASQUA, Claire TABOURET, Bernard FRIZE, Bertrand LAVIER, Fabienne VERDIER, Karl LAGASSE, Fabrice HYBER, DRAN, the French-American Nicole EISENMAN, the Sino-French WANG Yancheng, plus the highly successful comic-strip artist, Enki BILAL.

0

0